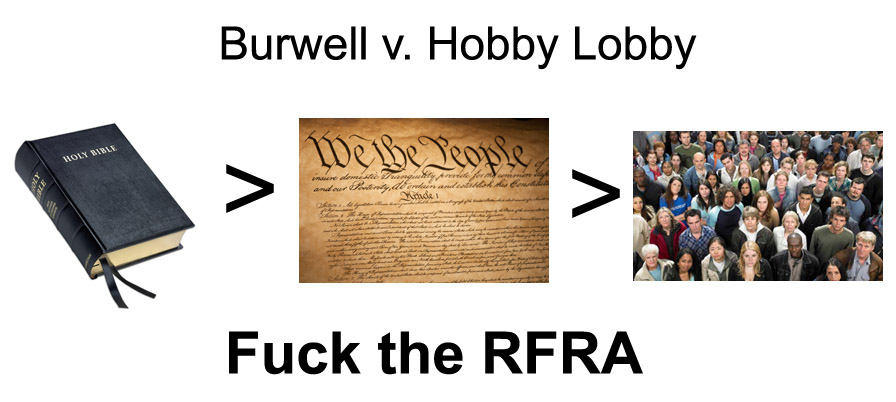

Folks on

the internet seem to not understand how Burwell v. Hobby Lobby happened. To explain, let's take a jaunt down legal

precedent lane.

In Reynolds

v. United States (1878) the Supreme court ruled that religious duty is not a defense to a criminal

indictment. You do not get to break a law, and defend yourself by claiming "religion".

To

permit this would be to make the professed doctrines of religious belief

superior to the law of the land, and, in effect, to permit every citizen to

become a law unto himself. Government could exist only in name under such

circumstances.

In

1878: Law > Belief A person can maintain religious beliefs, but

when those beliefs come into conflict with established law, the law wins.

In Employment Div. v. Smith (1990) the Supreme Court ruled that states are not required to

accommodate acts on grounds of religious belief. One remains subject to a "neutral law

of general applicability" despite

whether or not the neutral law conflicts with one's religious beliefs.

The

rule respondents favor would open the prospect of constitutionally required

religious exemptions from civic obligations of almost every conceivable kind --

ranging from compulsory military service, to the payment of taxes, to

health and safety regulation such as manslaughter and child neglect laws, compulsory

vaccination laws, drug laws, and traffic laws, to social welfare

legislation such as minimum wage laws, child labor laws, animal cruelty

laws, environmental protection laws, and laws providing for equality

of opportunity for the races. The First Amendment's protection of religious

liberty does not require this.

Further

But

to say that a nondiscriminatory religious practice exemption is permitted, or

even that it is desirable, is not to say that it is constitutionally required,

and that the appropriate occasions for its creation can be discerned by the

courts. It may fairly be said that leaving accommodation to the political

process will place at a relative disadvantage those religious practices that

are not widely engaged in; but that unavoidable consequence of democratic

government must be preferred to a system in which each conscience is a law unto

itself or in which judges weigh the social importance of all laws against the

centrality of all religious beliefs.

In

1990: Law > Belief. Exemptions for religious practice are

permitted, but not required by the Constitution.

Guess what happens next.

- The

purposes of this Act are

(1) to restore the compelling interest test as set forth in Federal court cases

before Employment Division of Oregon v. Smith and to guarantee its application

in all cases where free exercise of religion is substantially burdened; and

(2) to

provide a claim or defense to persons whose religious exercise is substantially

burdened by government.

This effectively overturned those previous rulings. After the RFRA, the government cannot limit a

person's exercise of religion, except in two cases.

(b)

EXCEPTION. -- Government may burden a person's exercise of religion only if it

demonstrates that application of the burden to the person --

(1) furthers a compelling governmental interest; and

(2) is the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling governmental

interest.

(c) The

Court assumes that the interest in guaranteeing cost-free access to

the four challenged contraceptive methods is a compelling governmental

interest, but the Government has failed to show that the

contraceptive mandate is the least restrictive means of furthering that

interest. Pp. 38–49.

When folks be bitching on Facebook, you may want to point out that the problem is not with SCOTUS, or Scalia changing his mind. The problem is religion, and the RFRA.

This may also be useful to cite whenever your naive Liberal friend spouts the wrongheaded maxim of "You can believe

whatever you want, so long as...".

When people believe X, they're going to try

to actualize X. No matter

how wrongheaded that X may be.

Where does this leave us?

To permit this would be to make the professed doctrines of religious belief superior to the law of the land, and, in effect, to permit every citizen to become a law unto himself. Government could exist only in name under such circumstances.